Announcing: Inngest Replay

The death of the dead-letter queue.

Dan Farrelly· 1/22/2024 · 7 min read

Production systems will fail. Incidents are inevitable.

An incident can take different forms. It can be a simple bug introduced somewhere in your codebase. Or, perhaps, an outage with an external resource like a third party API or a hosted database. Most developers have experienced them all.

For systems that need to be reliable, automatic retries are necessary. Often, to handle intermittent errors while continuing to reliably execute code, developers add queues, event streams, or other forms of durable execution to their architecture.

With these tools in hand, teams likely then implement automatic retries which help recover from temporary blips. But what about incidents that run for hours or days? Teams then need to implement a strategy for recovery themselves.

This is why we have built recovery tooling directly into our platform at Inngest. Today we announce Replay, the easiest way to recover from incidents with just a couple of clicks.

In this post we're going to look at some of the ways that teams implement recovery and share how we build Replay.

Queues

Message queues are no-brainer additions to an application architecture. By being able to run code asynchronously outside of the synchronous APIs in your application, code can be made more resilient and load can be better managed. So, let's look at how one can increase resiliency using queues.

The first step is to implement retries in your queue and worker. When a message fails to be processed, the worker should catch this error and, depending on the error type, decide whether to re-insert the message back into the queue or just log the failure. If the queue supports adding delays, you can give some time for a blip or minor outage to pass.

This is great — you now have some added resiliency, but what happens when there is a longer outage? If you keep re-inserting, your workers will continue to retry the same messages that will continue to fail. Because of this, you need to implement some sort of maximum retry logic so your workers can move on beyond this. Now, what happens to the messages that have hit maximum retries?

Messages that cannot be processed within a reasonable number of attempts need to be put somewhere so they can be addressed later. There are a few solutions here:

- Use a “dead-letter queue” if the queue of your choice supports this.

- Log/archive these messages in a database or in a log store.

- Drop the messages and do nothing. 🤷

Each of these approaches poses more questions on how to properly implement this. Often, teams cannot predict what types of failures will end up in these holding areas, so they don't set up any automated way to re-process these messages. The messages sit around, incidents happen and teams scramble to do something with the data (if they even have the data at all). Stress ensues. Over time you may have some halfway decent hacked-together scripts to recover; or maybe your team has an SRE that can do it properly, but most teams can't afford this luxury.

This is all to say that queues are great, but, at the end of the day, they're basic infrastructure leaving your team to implement retries, dead-letter queues, and logging/archiving then a custom recovery process.

Event streams

Similar to queues, event streams can enable teams to run asynchronous code with some reliability. Due to the nature that events within event streams are “facts” of what happened in the system, most event streams allow you to set up and configure an archive of events to some degree. You're in good shape, you have a historical record already!

Similar to queues, you need to implement a strategy for recovery with your historical events. You'll want to replay the events between two timestamps from the span of your incident. This will be some sort of script or API that you might create to re-publish events or, if supported, you can set up your consumer to read from an offset for a given timestamp.

The difference between events streams and message queues here is that some of your jobs may have already completed successfully during this time range. This means that you're likely to re-run work unnecessarily. This is one of the many reasons why idempotency is extremely important in systems like this. Your code must be idempotent: if it re-runs, it shouldn't cause a different result or duplicated results.

While event streams can make it relatively straightforward to set up an archive, your recovery strategy will not create itself. Teams committing heavily in event-driven architectures or event sourcing may invest in tooling early on in their adoption.This, however, takes effort and proper testing. Again, similar to queues, many teams may not build or rehearse this until they actually need it, leaving them prone to stressful situations and more work to recover from incidents.

Similar to queues, event streams are awesome, but teams need to invest the time and effort to build and test recovery strategies early on which is a considerable investment.

Inngest Replay

Developers should not have to reimplement these approaches for every new system that they build - they deserve better - and that is why we built Inngest.

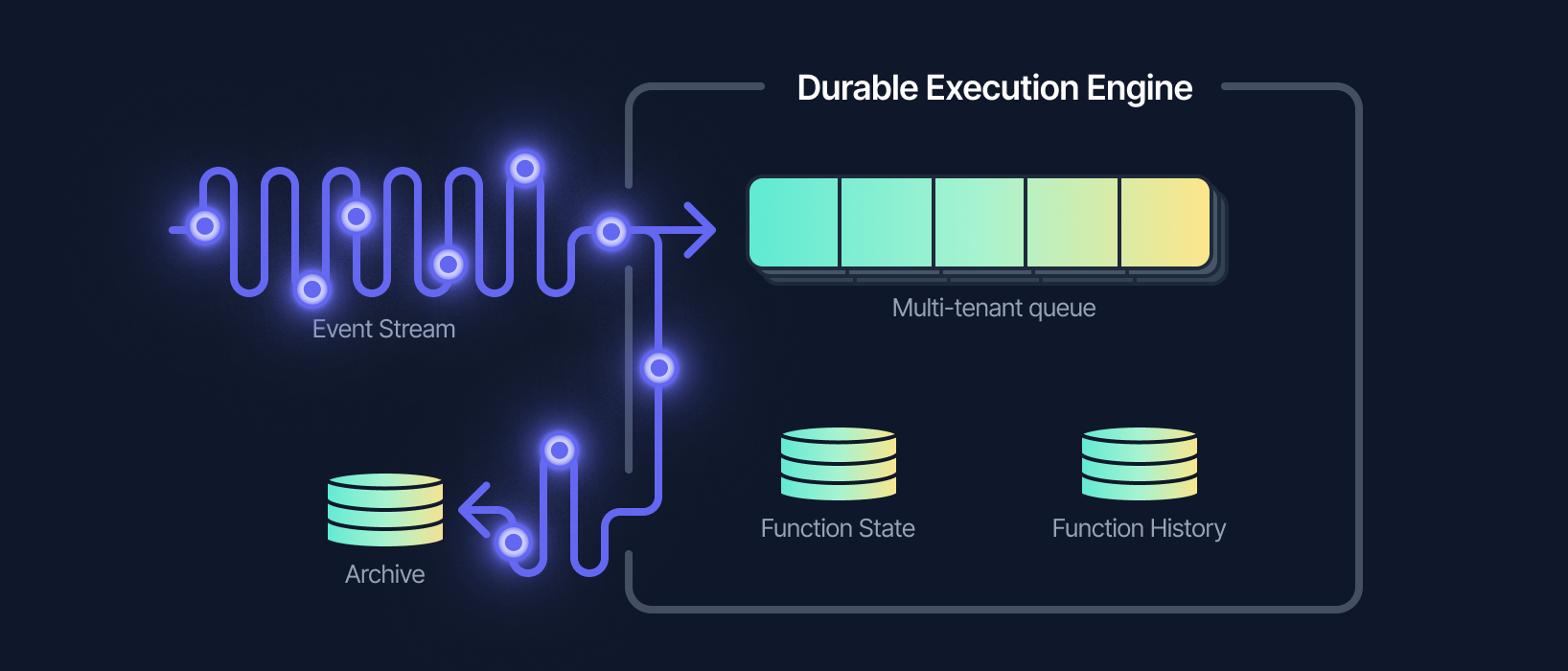

Inngest architecture combines event streams and queues with durable execution to create a single reliability layer. In the past we talked about the benefits of this approach including declarative job scheduling with events, code that pauses for additional data, and flow control. Today let's look at how this approach enabled us to build recovery tools directly into the platform.

Being built with an event stream, Inngest enjoys all the advantages mentioned above. In addition to the stream, Inngest stores all events that have been received so we can search hours, days, or weeks in the past.

Additionally, with a durable execution engine, Inngest is also responsible for executing your functions via HTTP. This means that every time a function is run, Inngest also stores the result of the job.

As Inngest's durable execution engine is built on top of queues, we can use this history to re-queue all of the jobs to re-execute the code that runs on your own infrastructure.

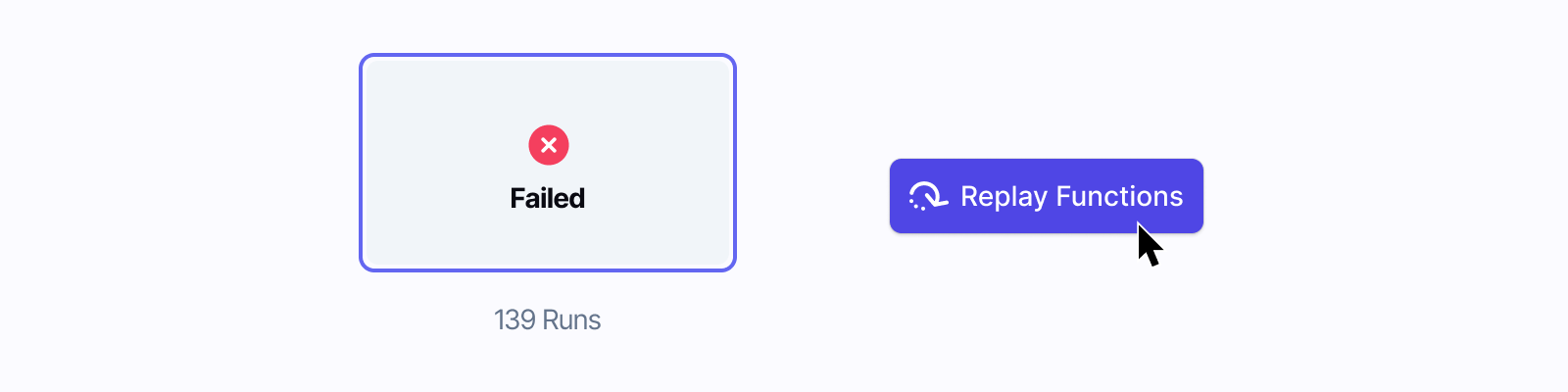

Combined together, we can easily query for all jobs between two timestamps and filter only jobs that failed (or were cancelled). It is as simple as selecting a function, the time range, and filter by the result of the job and clicking a button – no scripts needed!

We call this Replay. In other words, it's peace of mind that comes with every single Inngest plan, including the free tier. You can use Replay today in every Inngest account or learn how to use this feature in our guide.

Once you try it, we would love to hear what you think. Share your feedback or reach out on Discord!

What's next

We are only getting started.

In the future, we plan to expand Replay to event-replay which will make system-wide recovery simpler than ever before, especially in the case of systems relying heavily on fan-out jobs.

If you want to stay up to date with our product releases, subscribe to our newsletter or follow us on Twitter.

Every engineering team deserves faster, simpler recovery tools. Let us know what you think!